Global Conservation: How Collective Action Is Rewriting the Planet's Future

Humanity enters 2026 acutely aware that environmental stability is no longer a distant ideal but a precondition for economic security, social cohesion, and long-term health. Climate volatility, accelerating biodiversity loss, and the visible degradation of ecosystems across continents have transformed conservation from a niche concern into a central pillar of global strategy. Around the world, governments, corporations, Indigenous communities, scientists, and citizens are converging on a new paradigm in which protecting and restoring nature is inseparable from building resilient societies and competitive economies. For WorldsDoor, whose readers engage deeply with health, travel, culture, lifestyle, business, technology, and the wider world, these developments are not abstract policy shifts; they define how people live, invest, work, move, and eat in an era of profound environmental change.

Conservation in 2026 is characterized by a combination of scientific sophistication, ethical reflection, and practical innovation. International agreements have set ambitious targets, while local communities and city governments experiment with grounded, context-specific solutions. Digital technologies now allow real-time monitoring of forests and oceans, and financial markets increasingly recognize that ignoring ecological risk undermines long-term returns. At the same time, a renewed respect for Indigenous knowledge, youth activism, and community-based governance is reshaping how success is defined and who gets to participate in decision-making. This article examines the most significant global conservation success stories and structural shifts now unfolding, while reflecting on what they mean for the interconnected domains covered across WorldsDoor, from business and technology to culture, health, and the future of societies worldwide.

Biodiversity at a Turning Point: From Crisis to Coordinated Recovery

Biodiversity remains the bedrock of planetary health, underpinning food systems, clean water, climate regulation, and cultural identity. In the early 2020s, scientific assessments from organizations such as the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) made it clear that up to one million species were at risk of extinction. Yet, by 2026, the policy landscape has shifted in ways that, while insufficient on their own, provide a framework for coordinated recovery.

The Convention on Biological Diversity and its Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework remain central to this transformation. The commitment to protect at least 30 percent of land and ocean by 2030 has driven a wave of new protected areas, Indigenous and community conserved territories, and cross-border ecological corridors. Countries in Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas are revising land-use plans, strengthening environmental laws, and incorporating biodiversity indicators into national economic strategies. Readers interested in how these shifts intersect with global politics and regional dynamics can explore additional analysis on WorldsDoor's world section.

Practical examples of large-scale restoration are increasingly visible. Costa Rica's long-standing success in reversing deforestation through payment-for-ecosystem-services schemes has become a reference model for nations seeking to align conservation with rural development, tourism, and sustainable agriculture. In South America, initiatives such as the Trinational Atlantic Forest Pact are reconnecting fragmented habitats across Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina, allowing species to migrate and adapt to changing climatic conditions. In Europe, the expansion of transboundary reserves stretching from the Alps to the Balkans signals a recognition that wildlife does not respect political borders and that cooperation is essential for long-term resilience. To understand how such environmental strategies shape lifestyles, travel, and cultural identity, readers can visit WorldsDoor's environment hub, where conservation is framed as both ecological necessity and cultural opportunity.

Rewilding and Landscape-Scale Restoration: Europe and Beyond

The rewilding movement has matured from an experimental concept to a mainstream pillar of conservation policy, particularly across Europe but increasingly in North America, Asia, and parts of Africa. Organizations such as Rewilding Europe have demonstrated that returning large landscapes to more natural dynamics-by reintroducing keystone species and allowing natural processes to unfold-can generate cascading ecological and economic benefits. In regions such as the Iberian Highlands, the Danube Delta, and the Carpathian Mountains, the reintroduction of species like the European bison, lynx, and beaver has revitalized ecosystems that were once heavily degraded or depopulated.

The return of wolves to Germany, France, Italy, and parts of the United Kingdom has been both symbolically powerful and practically significant. As apex predators, wolves regulate herbivore populations, reducing overgrazing and enabling forest regeneration. This in turn improves soil quality, water retention, and carbon sequestration. Research by institutions including Oxford University's Wildlife Conservation Research Unit and other European universities has documented increased biodiversity and new income streams from eco-tourism and nature-based recreation. Similar rewilding concepts are now being applied in North America, where initiatives in the United States and Canada seek to restore bison populations and reconnect prairie and forest ecosystems, and in Asia, where efforts to protect snow leopards and tigers involve large-scale habitat corridors. For readers interested in how such projects intersect with cultural narratives, rural identities, and tourism experiences, WorldsDoor's culture section offers further perspectives.

Landscape-scale restoration is also taking root in the United Kingdom's uplands and lowlands, where privately owned estates and community trusts are experimenting with peatland restoration, native woodland regeneration, and river re-meandering. These projects are increasingly financed through a mix of public funds, philanthropic capital, and emerging biodiversity credit markets. In Germany, the Netherlands, and Scandinavian countries, rewilding is integrated with flood management and climate adaptation, demonstrating that ecological restoration can reduce disaster risk and infrastructure costs. This holistic approach aligns with the broader shift toward nature-based solutions promoted by organizations such as the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

Oceans in Recovery: Marine Protected Areas and Blue Economies

Marine conservation has advanced rapidly as governments recognize that ocean health underpins food security, climate regulation, and coastal economies. Over the past decade, the area of ocean under some form of protection has expanded significantly, driven by initiatives like the Global Ocean Alliance, the High Ambition Coalition for Nature and People, and philanthropic collaborations including the Blue Nature Alliance. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the 2023 adoption of the High Seas Treaty have provided legal mechanisms to safeguard marine biodiversity beyond national jurisdictions, a historic step for the governance of international waters.

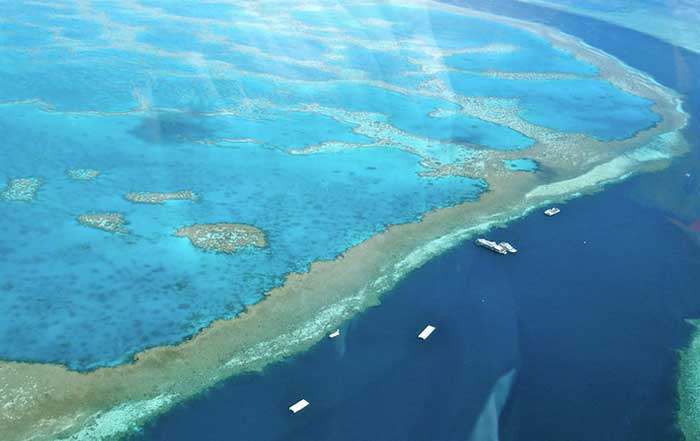

Examples of successful marine protection now span all major ocean basins. The Palau National Marine Sanctuary continues to serve as a model for small island states, demonstrating that large no-take zones can help rebuild fish stocks, attract sustainable tourism, and reinforce national identity. Australia's Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority has, despite ongoing climate pressures, scaled up coral restoration, water quality improvements, and local stewardship programs. These efforts are supported by advances in marine science and biotechnology, including research from institutions such as the Australian Institute of Marine Science and global networks coordinated through organizations like NOAA in the United States. Readers can learn more about how ocean conservation connects to wider sustainability debates through resources that discuss blue economies and sustainable fisheries management.

In Southeast Asia, the Coral Triangle region-encompassing Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, and neighboring countries-has seen expanded networks of marine protected areas and community-managed reserves that blend traditional ecological knowledge with modern science. Mangrove restoration projects in Indonesia, Vietnam, and Thailand are increasingly recognized by climate finance mechanisms for their carbon sequestration potential, while also providing storm protection and nursery habitats for fisheries. For a broader view of how such initiatives relate to sustainable development pathways, WorldsDoor's sustainable section explores the interplay between environmental integrity and long-term economic opportunity.

Africa's Conservation Renaissance and Community Leadership

Across Africa, conservation has undergone a profound transformation, moving away from exclusionary models toward approaches that prioritize community rights, livelihoods, and shared governance. Countries such as Kenya, Namibia, Botswana, Rwanda, and South Africa have embraced community conservancies, transfrontier parks, and mixed-use landscapes that integrate wildlife management with agriculture, tourism, and pastoralism. These models increasingly inspire interest in regions from Latin America to Asia, where balancing biodiversity protection with local development is a central challenge.

In Kenya, organizations like the Northern Rangelands Trust (NRT) have facilitated the creation of community conservancies that collectively manage millions of hectares. These conservancies support populations of elephants, rhinos, lions, and endangered species such as Grevy's zebra, while providing income through eco-tourism, sustainable livestock programs, and carbon projects. The Lewa Wildlife Conservancy, recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, has become emblematic of integrated conservation, combining anti-poaching operations, education programs, and community health services. Partnerships with global organizations including Save the Rhino International, World Wildlife Fund (WWF), and regional agencies have significantly reduced poaching and improved local security.

Namibia's communal conservancy system, often cited by institutions such as the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), continues to demonstrate that devolving rights over wildlife to local communities can increase both biodiversity and household incomes. In southern Africa, transboundary initiatives such as the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA) link Botswana, Namibia, Angola, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, enabling wide-ranging species like elephants to move across borders while generating revenue from nature-based tourism. These successes have implications for social stability, land rights, and rural development, themes that are further explored in WorldsDoor's society coverage, where conservation is examined as a driver of equity and inclusion.

Technology as a Force Multiplier in Conservation

By 2026, technology has become one of the most powerful enablers of effective conservation. Satellite imagery, remote sensing, drones, artificial intelligence, and genomics are now deeply integrated into monitoring, enforcement, and planning. Platforms such as Global Forest Watch, supported by the World Resources Institute (WRI), offer near-real-time deforestation alerts, allowing governments, NGOs, and even journalists to identify illegal logging within days rather than months. Google Earth Engine and similar cloud-based geospatial tools make it possible for researchers and policymakers to analyze decades of land-use change, climate trends, and ecosystem health at global and local scales.

Artificial intelligence increasingly supports predictive modeling of poaching hotspots, wildfire risk, and invasive species spread. Projects like Wildbook use computer vision to identify individual animals-from whale sharks to giraffes-based on unique patterns, enabling non-invasive population tracking. Environmental DNA (eDNA) techniques allow scientists to detect species presence in rivers, lakes, and oceans by analyzing tiny fragments of genetic material in water samples, making biodiversity surveys faster and less intrusive. For readers interested in how these technologies intersect with broader digital innovation and ethical debates, WorldsDoor's technology section provides ongoing coverage of AI, data, and their societal implications.

On the financial side, blockchain-based platforms and digital registries are being tested to increase transparency in carbon markets and biodiversity credits. Standards bodies such as Verra and emerging technology firms have been working to improve verification of carbon sequestration and ecosystem restoration projects, responding to criticism about "greenwashing" and questionable offsets. While these systems are still evolving, the direction of travel is clear: data-rich, verifiable, and publicly accessible information is becoming the norm in conservation finance. This shift is closely linked to broader trends in sustainable business and impact investing discussed in WorldsDoor's innovation section.

Corporate Stewardship and the Mainstreaming of Nature-Positive Business

Corporate sustainability has moved beyond voluntary pledges and marketing narratives to become a core strategic issue for global firms. Investors, regulators, and consumers in regions from North America and Europe to Asia-Pacific increasingly expect companies to demonstrate credible progress on climate, biodiversity, and social equity. The Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), launched to complement climate-focused frameworks such as the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), is encouraging businesses and financial institutions to assess and disclose their dependencies and impacts on nature.

Companies like Unilever and Patagonia remain high-profile examples of integrating environmental stewardship into corporate DNA, but they are no longer outliers. Large technology firms such as Apple and Microsoft continue to invest heavily in renewable energy, circular design, and nature-based carbon removal. Financial groups including HSBC, BNP Paribas, and asset managers like BlackRock have strengthened policies on deforestation, coal financing, and biodiversity risk, partly in response to pressure from shareholders and civil society. Regulatory bodies in the European Union, the United States, the United Kingdom, and other jurisdictions are tightening disclosure rules, making it more difficult for companies to ignore environmental liabilities.

For business leaders and professionals, this evolving landscape presents both risk and opportunity. Supply chains are being reconfigured to reduce land-use impacts, water consumption, and pollution. Nature-positive design is increasingly seen as a source of competitive advantage, especially in sectors such as food, fashion, tourism, and real estate. Readers seeking a deeper understanding of these shifts can explore WorldsDoor's business section, where corporate case studies, regulatory developments, and investor trends are analyzed through the lens of long-term resilience and ethical governance.

Cities as Engines of Green Transformation

Urban areas, once viewed primarily as drivers of environmental degradation, are emerging as critical arenas for conservation and climate resilience. With more than half of the global population living in cities-and urbanization accelerating in Asia, Africa, and Latin America-urban planning decisions today will shape ecological outcomes for decades. Leading cities in Europe, North America, and Asia-Pacific have adopted green infrastructure strategies that integrate parks, wetlands, street trees, and nature-friendly design into dense built environments.

Cities such as Singapore, Copenhagen, Stockholm, Melbourne, and Vancouver have become reference points for climate-smart urbanism. Singapore's extensive network of green corridors, vertical gardens, and restored waterways demonstrates how biodiversity can thrive in a highly urbanized setting while enhancing public health and livability. Scandinavian capitals have embraced district heating, cycling infrastructure, and blue-green corridors that manage stormwater while providing habitat for birds and pollinators. In China, the "sponge city" concept, piloted in locations including Wuhan and Shenzhen, uses permeable surfaces, wetlands, and retention basins to reduce flooding and improve water quality.

In North America and Europe, the transformation of post-industrial sites into ecological and social assets-such as New York City's High Line, the Chicago Riverwalk, and river restoration projects in Germany and the Netherlands-illustrates how conservation and cultural regeneration can go hand in hand. In Africa and South America, urban forestry initiatives in Nairobi, Johannesburg, and Bogotá are addressing heat stress, air pollution, and social inequality through equitable access to green spaces. These developments intersect with lifestyle, health, and social cohesion, themes explored further in WorldsDoor's lifestyle coverage, where urban living is increasingly framed through the lens of nature-connected design.

Indigenous Knowledge, Ethics, and the Reframing of Conservation

One of the most significant conceptual shifts in global conservation has been the growing recognition that Indigenous peoples and local communities are not stakeholders to be consulted at the margins, but rights-holders and essential leaders in environmental governance. Studies by organizations such as IPBES and FAO have shown that lands managed by Indigenous communities often have equal or higher levels of biodiversity than formally protected areas, despite receiving fewer resources and less recognition.

In the Amazon Basin, Indigenous federations in Brazil, Peru, Colombia, and other countries are increasingly supported by satellite monitoring, legal advocacy, and international solidarity networks such as Amazon Watch and the Rainforest Foundation. These alliances have helped slow deforestation in key territories, challenge illegal mining and logging, and assert land rights in courts and international forums. In Australia, the expansion of Indigenous Protected Areas and the revival of cultural burning practices have reduced wildfire risk and supported the recovery of fire-adapted ecosystems, with support from the Australian government and scientific institutions.

Ethical frameworks such as "Two-Eyed Seeing"-which emphasizes learning from both Indigenous and Western knowledge systems-are gaining influence in universities, research institutes, and policy processes in Canada, the United States, and Scandinavia. These approaches challenge purely technocratic models of conservation and foreground questions of justice, identity, and historical responsibility. For readers who wish to explore how ethics and culture shape environmental choices, WorldsDoor's ethics section and culture section examine these dimensions in depth, highlighting stories where conservation becomes a vehicle for reconciliation and shared futures.

Youth, Education, and the Next Generation of Environmental Leadership

The global youth climate and conservation movement has matured into a sophisticated network of organizations, campaigns, and entrepreneurial ventures. Activists inspired by figures such as Greta Thunberg have expanded their focus from protests to policy engagement, strategic litigation, and innovation. Youth-led groups in Europe, North America, Africa, Asia, and Latin America are influencing national climate laws, corporate practices, and international negotiations, including the UNFCCC Conferences of the Parties.

Education systems are gradually responding to this generational shift. In the United Kingdom, Germany, the Nordic countries, and parts of North America, environmental literacy is now integrated into curricula from primary school through university. In Asia and Africa, partnerships between ministries of education, NGOs, and international organizations are expanding access to climate and conservation education, including vocational training in renewable energy, sustainable agriculture, and ecosystem restoration. Online platforms such as Coursera, edX, and university-led initiatives from Yale, Stanford, and Imperial College London provide global access to high-quality courses on sustainability, climate science, and environmental law. Readers can explore how these educational transformations are reshaping societies on WorldsDoor's education page, where learning is framed as a catalyst for ethical and practical change.

Youth entrepreneurship is also flourishing, with start-ups in regions from Europe and North America to India, Kenya, Brazil, and Southeast Asia developing solutions for plastic reduction, regenerative agriculture, biodiversity monitoring, and clean energy. Programs such as UNEP's Young Champions of the Earth and university climate accelerators provide mentorship, funding, and visibility, helping young innovators move from prototypes to scalable impact. This generational energy is not only pushing institutions to act faster; it is redefining what leadership looks like in the 21st century.

Measuring Impact and Navigating the Road Ahead

As conservation becomes more deeply embedded in policy, finance, and corporate strategy, the question of how to measure success grows more complex. Traditional indicators-such as the number of protected areas or the population of flagship species-remain important but are no longer sufficient. Modern conservation metrics now encompass ecosystem integrity, connectivity, carbon storage, water security, and community well-being. Tools like the Living Planet Index, produced by the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and WWF, track vertebrate population trends, while the Global Biodiversity Outlook synthesizes data on progress toward international targets.

Remote sensing data from agencies like NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) underpin global monitoring of forest cover, glacier retreat, ocean temperatures, and more. At the same time, social indicators-ranging from secure land tenure and local income to participation in decision-making-are increasingly recognized as essential to evaluating whether conservation is just and durable. These multiple dimensions of impact align with the integrated perspective that WorldsDoor brings to its coverage, connecting environmental outcomes with health, food systems, society, and global governance.

Looking forward from 2026, the planet is still far from a safe ecological trajectory. Greenhouse gas concentrations remain high, many ecosystems are under severe stress, and the implementation gap between policy commitments and on-the-ground action is significant. Yet the conservation success stories and systemic shifts emerging across continents demonstrate that decline is not inevitable. When science, ethics, innovation, and inclusive governance align, degraded landscapes can be restored, species can recover, and economies can thrive in ways that respect planetary boundaries.

For readers of WorldsDoor-whether in the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Canada, Australia, France, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, Switzerland, China, Sweden, Norway, Singapore, Denmark, South Korea, Japan, Thailand, Finland, South Africa, Brazil, Malaysia, New Zealand, or any other part of the world-the implications are both global and personal. Choices about travel, diet, investment, education, and lifestyle collectively shape the demand signals that governments and corporations respond to. By staying informed through platforms like WorldsDoor, engaging with evidence-based perspectives, and supporting initiatives that prioritize regeneration over extraction, individuals and organizations alike can contribute to a future in which conservation is not an emergency response but a defining feature of a flourishing, equitable, and resilient civilization.